Bird Conservancy research biologist Rob Sparks with Black Swift. Photo by Todd Patrick

We are drawn to the Black Swift because they remind us of wild places and the rugged terrain they inhabit. Flying over vast expanses, streams and mountains, they represent nature, wild and untamed. We love and value these places and our natural heritage inherited from our ancestors, and hope to leave them intact for future generations to explore. The story of the Black Swift is one of inspiration, discovery and challenges—and an urgent call to action if this special bird is going to be part of that future.

In 1881, Frank M. Drew was the first to document Black Swifts in Colorado flying high over the San Juan Mountains. This species wasn’t confirmed nesting in the state until 1949 by Owen Knorr. Almost five decades since the first nest was found, there was still very little known about this species. In 1997, Bird Conservancy (then RMBO) collaborated with the U.S Forest Service to start an inventory and documented 103 nest sites in Colorado. Today, technological advances and new tools are helping take our research to new heights, revealing more about Black Swift ecology than ever before.

Movement ecology

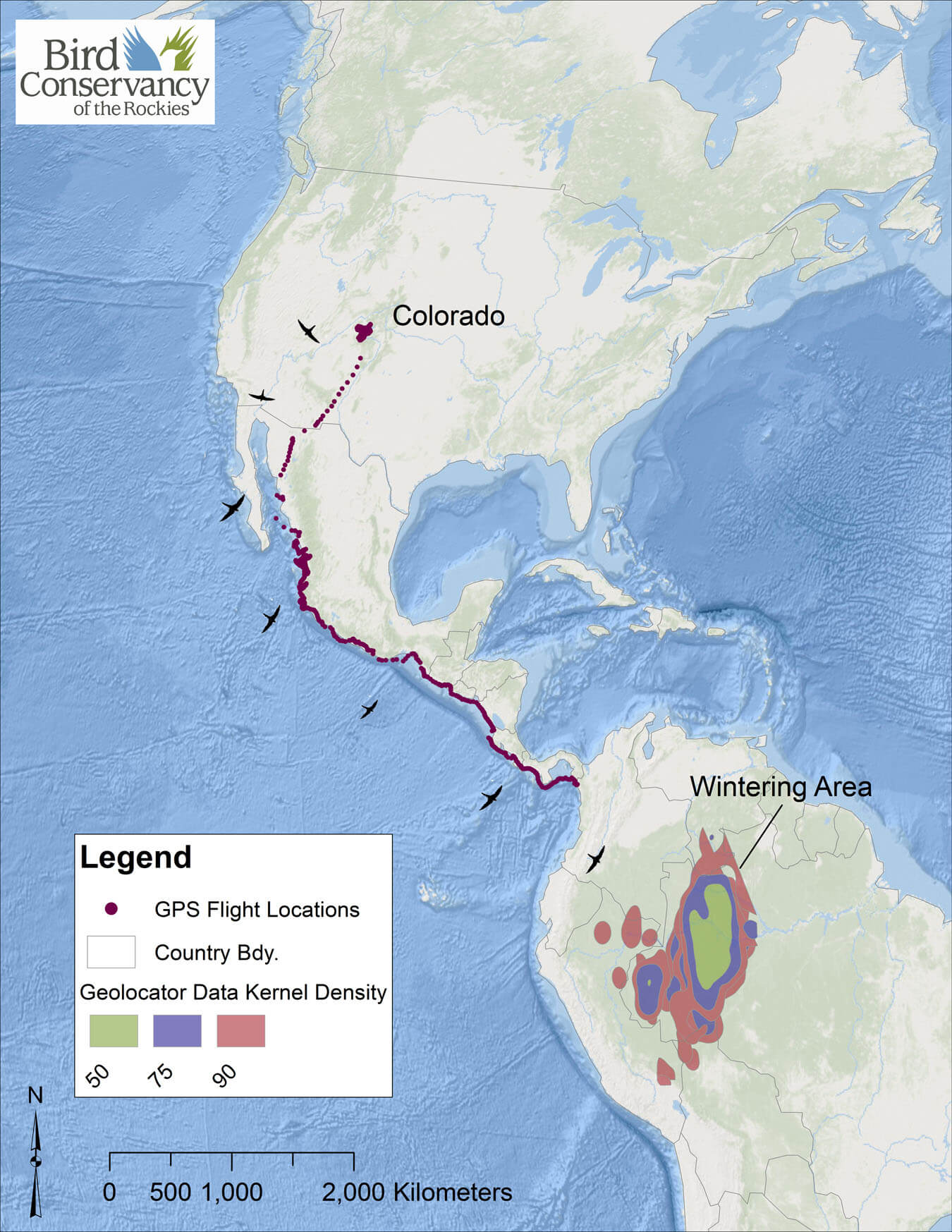

Together with our research team, I am leading an effort to understand the movement ecology of the Black Swift during the breeding season, which is currently unknown. Our objective is to learn more about their foraging patterns and identify daily foraging routes, gaining an understanding of their flight behavior, foraging hotspots and habitat relationships. A secondary objective is obtain more precise migration and wintering locations. This information is critical to guiding conservation efforts for the species. In 2017, myself, Forest Service biologist Kim Potter and citizen scientist Carolyn Gunn, as well as Bird Conservancy Science Director Luke George, attached Global Positioning System (GPS) tags to five swifts across sites in western Colorado. In 2018, we set out to recapture these birds—a feat that required patience and perseverance.

GPS tag. Photo: Jack Ferguson

Return of the swift

During a clear summer evening, Bird Conservancy’s Banding Coordinator Colin Woolley and I arrived at Box Canyon State Park, perched above the town of Ouray, Colorado. We were greeted by Sue Hirshman., another devoted Black Swift conservationist. Sue informed us that the same nest we deployed a GPS tag at last year was active, but she was not able to determine if the adult swift with the GPS tag survived its long migratory trip back from South America. As the sky darkened, we discussed our recapture plans, eager to see if the adult with the GPS tag was on the nest.

Rob Sparks setting up a mist net. Photo: Jack Ferguson

We edged along the steel walkway, stopping to look at the nest before descending down to the canyon floor. Swifts were chattering overhead, streaming in and out of the canyon. The nest sits on a knob protruding from the canyon wall. As our headlights shined over the nest, we saw a fledgling, then an adult with an antenna sticking upwards from its back. We looked at each other in excitement, switching our headlights to red before going further in order to avoid disturbing the birds.

On the canyon floor, the sound of the crashing waterfall was deafening. We carefully set up wildlife ladders and readied our equipment. I slowly climbed up the ladder, and used a hand-held net to recapture the tagged bird. The male swift appeared strong and healthy. We removed the GPS tag, took some measurements, and returned it to its nest. The data on this tag will provide answers to basic foraging questions new to science.

Conservation connections

In 2012, Bird Conservancy and partners discovered the annual migratory path and core wintering destination of the Black Swift, which is in the lowland rainforests of Brazil. Since then, we’ve continued our efforts to learn more about their movement ecology, such as flight and foraging patterns, to help inform conservation needs. The Northern Black Swift is an aerial insectivore that spends most of its time on the wing foraging for insects. Its cryptic nature and difficult-to-access nesting locations make it one of the least understood bird species in North and Central America. Black Swifts nest in remote areas on wet rock faces, in moist coastal caves or on ledges near waterfalls.

Designated as a species of continental concern by in the U.S and Canada, the species has lost 94% of its population according to Breeding Bird Survey data. Unfortunately, the wider guild of aerial insectivores including swallows, martins, nightjars, whip-poor-wills and flycatchers are also experiencing steep population declines across North America. This region-wide pattern implies that large scale factors are causing the decline. There is an urgent need to fill information gaps when it comes to the Black Swift and other aerial insectivores.

Designated as a species of continental concern by in the U.S and Canada, the species has lost 94% of its population according to Breeding Bird Survey data. Unfortunately, the wider guild of aerial insectivores including swallows, martins, nightjars, whip-poor-wills and flycatchers are also experiencing steep population declines across North America. This region-wide pattern implies that large scale factors are causing the decline. There is an urgent need to fill information gaps when it comes to the Black Swift and other aerial insectivores.

Zapata Falls

We retrieved a second GPS tag during our last recovery attempt at Zapata Falls, in the rugged Sangre de Cristo Mountains next to the Great Sand Dunes National Park. Our walk to the falls started before sunrise under the moonlight, with the scent of pinyon and juniper trees in the air. After hiking for a few minutes, a stream leads us up to our banding site.

At this site, we used a double-stacked net set across a stream at the entrance of the canyon, reaching a height of 21 feet. We raised the nets just before sunrise while swifts foraged in the moonlight overhead, catching moths. Not long after, we captured a handful of swifts and we’re excited to see one with an antenna land in the net. We carefully extracted the bird, untangling it from the net before removing the GPS tag.

Colin Woolley and Rob Sparks extracting a Black Swift. Photo: Madeline Jorden

Foraging flights

We are still analyzing the data from the recovered tags, but the foraging patterns during the breeding season that have been revealed are exciting. Early results suggest Black Swifts travel an average of 160 km daily while foraging at an average elevation of 10,200 feet. These distances and heights exceed by far foraging movements covered by most landbirds.

On the wing

During our recapture efforts, independent researcher Greg Levandoski, along with myself and Colin also deployed wing activity devices to determine whether this species performs aerial roosting, an incredible adaptation where swifts sleep while on the wing, spending months in the air without landing. We are collaborating with the same team that made the aerial roosting discovery for their European counterparts the Common Swifts. We hope to recapture these wing activity devices and a few more GPS tags next year. Our findings will be part of a much needed conservation blueprint for the Black Swift.

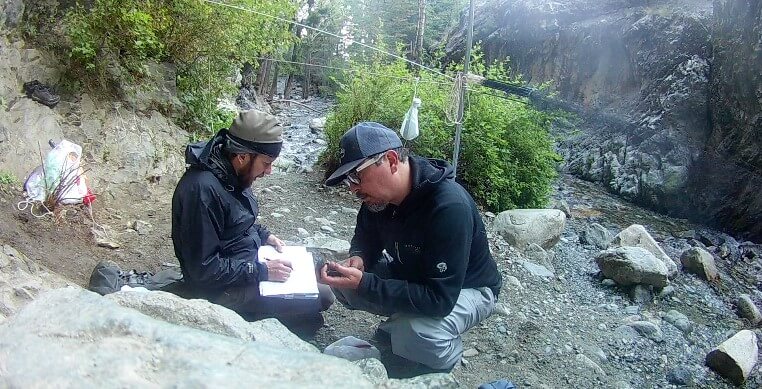

Greg Levandoski and Rob Sparks banding. Photo: Rob Sparks

This animation represents one foraging flight from Box Canyon during the breeding season. The flight starts with a series of sharp turns characteristic of its morning flight and heads south before flying west, then north. Eventually returning back to the nest site towards the end of the day. The flight is represented by GPS locations can be characterized by step lengths (distance between points) and turning angles. When there are a few sharp turning angles this likely represents a foraging event.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to all our donors and funders for making this research possible. Special recognition to our research team, citizen scientist Carolyn Gunn, USFS biologist Kim Potter and longtime Black Swift conservationist Sue Hirshman. for all their valuable contributions and continued support. The Lois Webster fund and the Denver Field Ornithologists were an invaluable funding source and provided much needed funds for 2018 field work. Jason Beason was influential in the initial stages of the project and Rich Levad a guiding force.

For more information about our Black Swift monitoring and research efforts, please contact Rob Sparks.

Your support fuels our efforts to help understand the conservation footprint needed to conserve Black Swifts in Colorado and beyond. Together, we can ensure a future where the ‘Coolest Bird’ continues to soar through the skies! With your gift today, you can help us retrieve more GPS tags and continue unlocking the mysteries surrounding this inspirational bird.

Black Swifts have inspired a love of avian conservation in many people. In this video, Bird Conservancy board member Jack Ferguson shares his personal story about how one tiny bird has sparked a lifelong interest in birds.

Black Swift nesting on a canyon wall in Ouray, Colorado. Photo taken in June of 2013 in Box Canyon Falls, Colorado by Julie Price.