“In our time, no foreign army has ever occupied American soil—until now.”

(tagline from the movie poster for 1984’s Red Dawn)

The United States spent an estimated $8 trillion to keep the Soviet Union at bay during the Cold War. The Soviets spent almost as much in return, and the tensions found their way into popular culture. In the 1980s, Russian invasions were a popular storyline in American movies. Red Dawn depicted resistance fighters, led by heartthrob Patrick Swayze, in a valiant fight to save their town, high school and hockey field from the Reds. Wolverines!!! .Meanwhile, as the fictional invasions were taking place on the big screen, a silent invasion was happening for real around the world.

An invasion, but not the kind we imagined

For decades, aided by global trade and transportation, species from distant lands have been finding their way to new homes at a record pace. Often these relocations were intentional, sometimes an accident. No shots were exchanged, no explosions occurred. But the consequences are just as messy and problematic. Without the predators and natural controls they evolved with to keep them in check, these invaders reproduced and spread, often displacing native plants and animals. We refer to the plant version of these bad guys as noxious, or invasive, weeds. In western states like Colorado, the most notorious offenders include leafy spurge, cheatgrass, musk thistle, spotted knapweed, diffuse knapweed and (gasp!) Russian knapweed.

Natasha and Boris may appreciate the showy purple blooms of Russian knapweed, but those pretty flowers distract from its less desirable qualities. Photo by Stan Shebs, CC by 2.0 via Wikipedia.

No beating around the bush—living in America is good for Russian knapweed

Russian knapweed (Rhaponticum repens) was originally introduced to North America in 1898. Put simply, this plant seems to love its adopted country—a little too much! Since arriving, it has spread to Colorado, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming and other states. Russian knapweed thrives in moist riparian habitat and the floodplains of streams and rivers, but it is highly adaptable. In southeast Colorado, where it is considered a B-List noxious weed, it is becoming more common in arid rangelands that have been heavily disturbed. Once established, it forms dense infestations and is extremely difficult to remove.

A weed with no agricultural or ecological value

Grazing animals generally avoid the weed because of its bitter flavor, and it is poisonous to horses. The plant produces toxic chemical compounds that prevent other species from growing nearby, outcompeting native grasses and forbs. This degrades important wildlife habitat for both riparian and grassland bird communities that rely on native vegetation for foraging, cover or nesting. The removal of Russian knapweed opens the door for the return of native grasses and flowering plants, benefiting not only birds but also insects, reptiles, small mammals and livestock. Russian knapweed and other invasive pests not only wreak havoc on natural habitats, but they also result in huge economic impacts. Private landowners, government agencies and non-governmental organizations spend millions of dollars each year just trying to control the spread.

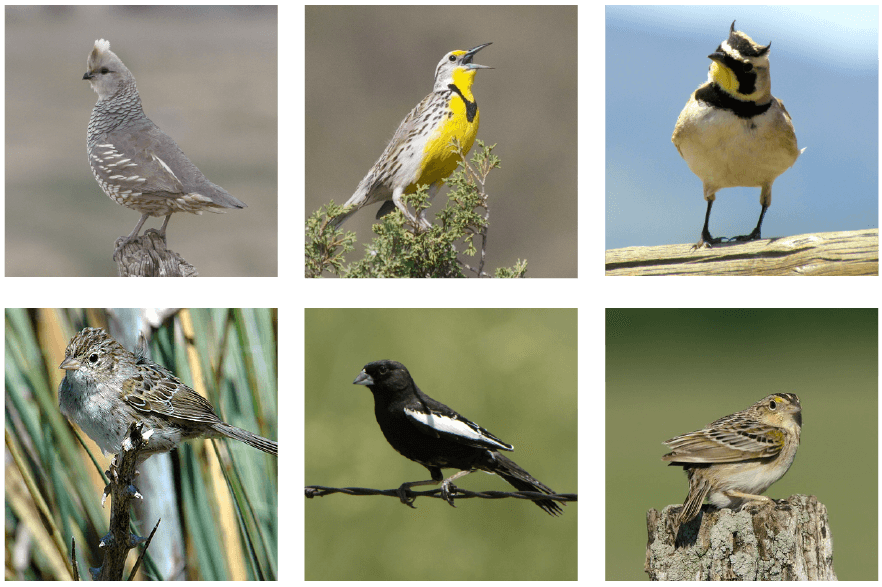

Ground-nesting grassland birds like Scaled Quail (Aaron Driscoll) Western Meadowlark (Michelle Desrosiers), Horned Lark (Deanna Beutler), Lark Bunting (Bill Schmoker), Cassin’s Sparrow (Bill Schmoker) and Grasshopper Sparrow (Dominic Sherony) stand to benefit greatly from the removal of Russian knapweed.

Colluding with Russian…wasps?

A new helper is being enlisted in the fight to eradicate Russian knapweed, and it hails from Mother Russia herself: Russian knapweed gall wasp (Aulacidea acroptilonica). The tiny insects feed exclusively on Russian knapweed, which is its “host” plant. This ensures they won’t harm other surrounding plant species and acts as a natural, biological control (referred to as a biocontrol) on the weed. In 2008, the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) led an environmental assessment using this species as a biocontrol, followed by testing in Montana in 2009. The results were extremely promising.

Russian knapweed gall wasp.

Photo by RiversEdge West.

Even the tiniest flea can drive a big dog crazy

This Russian proverb describes perfectly how the tiny gall wasp helps bring down knapweed. Adult wasps lay their eggs on new growth during the spring. The larvae hatch and begin feeding on plant tissue, which forms galls—tumor-like growths that also serve as an incubating ‘container’ for the larvae. The larvae overwinter inside the galls, sometimes for up to two years. Inside, they undergo the transformative process called pupation, similar to butterflies and moths. They emerge from the galls as wasps and the process begins again. The adult stage lasts only about one week. The wasp attacks stress the plant, reducing flowering and seed production which helps suppress the growth and spread of knapweed.

Send in the paratroopers!

Send in the paratroopers!

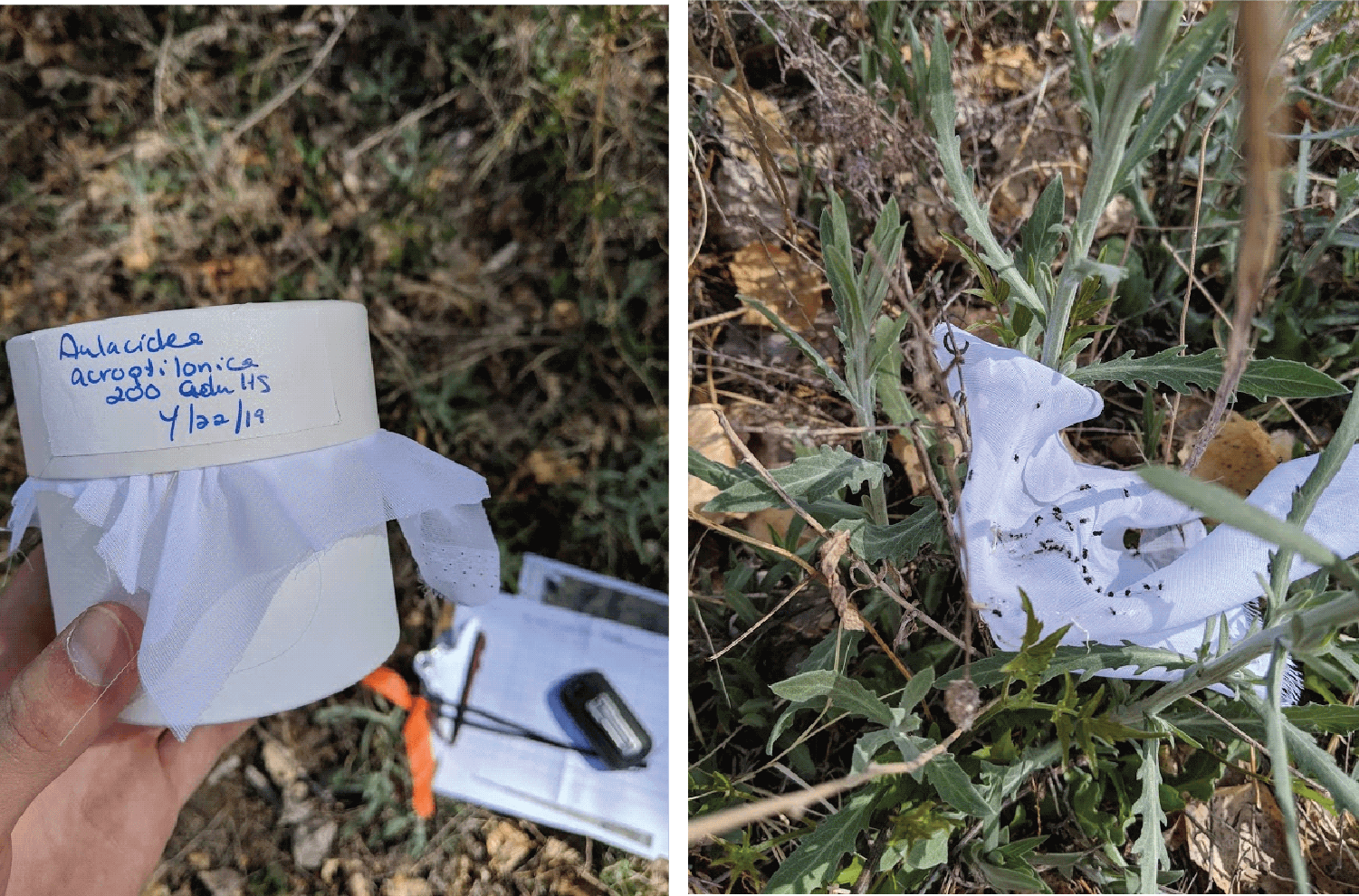

Bird Conservancy’s Ryan Parker (Private Lands Wildlife Biologist) and Patty Knupp (NRCS Area Biologist) recently spent a day releasing gall wasps on Russian knapweed-infested areas in Colorado’s Crowley and Bent counties. This is the first large-scale release effort in SE Colorado, with 11 release sites total and roughly 200 wasps per site. Palisade Insectary provided the wasps, which were grown in their facility. Galls should be observed in the stems of the Russian knapweed within weeks of the wasps being released. Stay tuned for updates on their progress!

Good to the last bug?

It will take a couple of seasons to know how much impact these wasps are making on Russian knapweed, and they are unlikely to be the silver bullet to solving this problem. Similar to Cold War military strategy, biocontrols are just one of a diverse array of “weapons” in the war against weeds. Chemical and mechanical methods of eradication will continue to be critical. Meanwhile, other biocontrols such as the Russian knapweed gall midge, originally from China, are also being tested by many agencies and organizations across the west. Of course, the most cost-effective way to manage it is to prevent it from getting established in the first place. As MrLundScience sings in his Invasive Species Science Rap, “With every seed that drops, I’m even harder to stop.” So keep an eye out for those knapweeds and their troublemaking friends. The invasion is still happening!

Ryan Parker (based in Rocky Ford, CO) is employed by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies with funding support from NRCS, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Records-Johnston Family Foundation, Inc.

This project is made possible through the support and collaboration of