Lessons Learned from Former Stewardship Biologists

In the northwestern corner of Colorado, rolling hills and open sagebrush plains are home to migratory herds of elk and leks of displaying Greater Sage-grouse. Eighteen miles north of the small town of Craig in Moffat County lies the family-run Visintainer Sheep Company. The Visintainers and their company have exemplified the mutual benefits and success that comes from coupling ranching operations with a conservation mindset, and have worked with partners including Bird Conservancy of the Rockies to tailor their management practices and cultivate high quality wildlife habitat on their land. Brandon Miller, a Bird Conservancy Private Lands Wildlife Biologist (PLWB), helped the Visintainers enroll in the Sage Grouse Initiative ̶ a program that proactively conserves western rangelands and wildlife ̶ more than ten years ago.

Left to right: Gary Visintainer (landowner), Brandon Miller (Bird Conservancy of the Rockies), Bob Timberman (USFWS Partners Program), Dean Visintainer (landowner – RIP), and Bill Noonan (retired USFWS Partners Program) during a 2011 Sage Grouse Initiative field tour in Moffat County, Colorado. Photo by Seth Gallagher, 2011.

Once Brandon moved on from his PLWB position, he passed the torch to our biologist Becky Jones, who continued to work on projects benefiting Sage-grouse, Sharp-tailed Grouse, and big game on the Visintainer ranch. Becky recalls that working with the Visintainers made a great impression on her. While she was able to provide access to knowledge, tools, and resources through her role at Bird Conservancy, Becky felt that she learned much more from them through their deep connection to the land. We recently reached out to some of our former biologists like Becky to chat with them about their time as Bird Conservancy Private Lands Wildlife Biologists.

The Visintainer Sheep Company in Moffat County, Colorado has long partnered with organizations including Bird Conservancy to manage habitat for wildlife. Photo by Jessie Reese.

The Private Lands Wildlife Biologist (PLWB) program is a crucial pillar in Bird Conservancy’s three-pronged approach to avian conservation through science, education, and stewardship. As scientists became aware of alarming declines in grassland birds in the western Great Plains region over the past several decades, Bird Conservancy realized that working with private landowners would be key to influencing habitat management in grasslands. After spending a few years developing outreach tools for landowners like habitat management guides, bird identification booklets, and workshops series, Bird Conservancy began to partner with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in 2008 to co-employ Private Lands Wildlife Biologists. Our biologists work in local NRCS field offices, often in rural and remote communities, across the western Great Plains and eastern Rocky Mountains. They help landowners improve habitat for wildlife through interventions such as thinning overstocked forests, restoring streams and wetlands, removing shrubs encroaching in grasslands, treating invasive species, and developing rotational grazing systems. Their jobs are complex, challenging, and incredibly rewarding.

Reconnecting with Old Friends

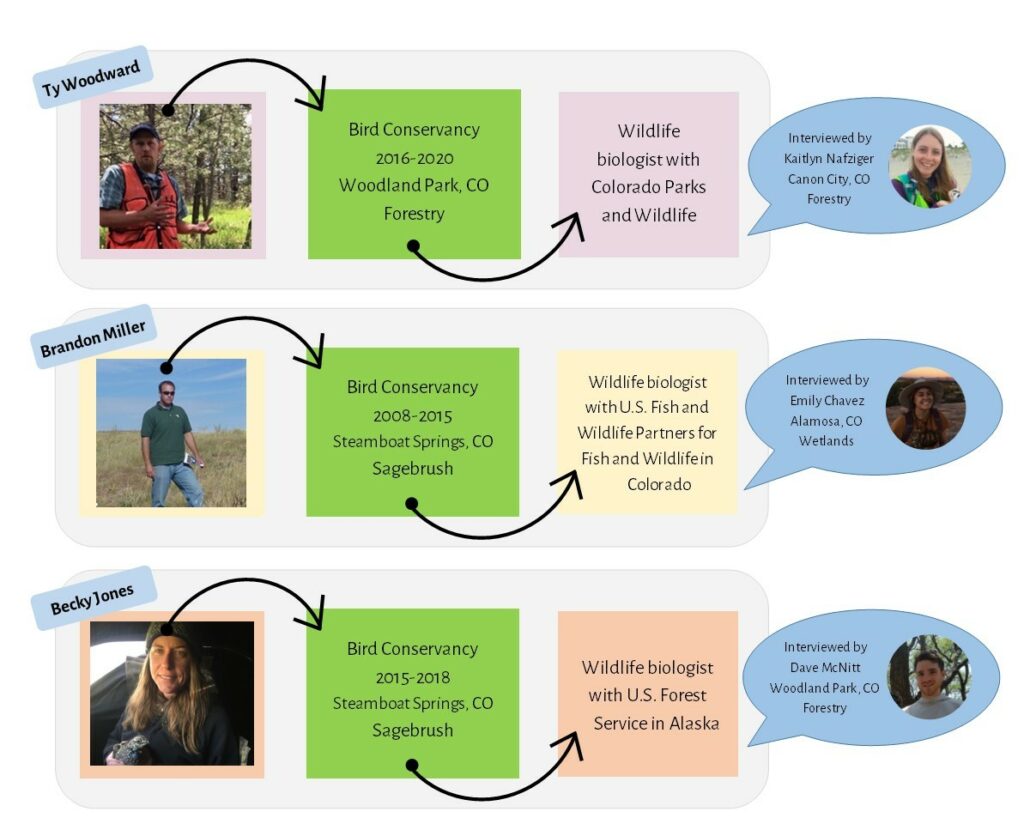

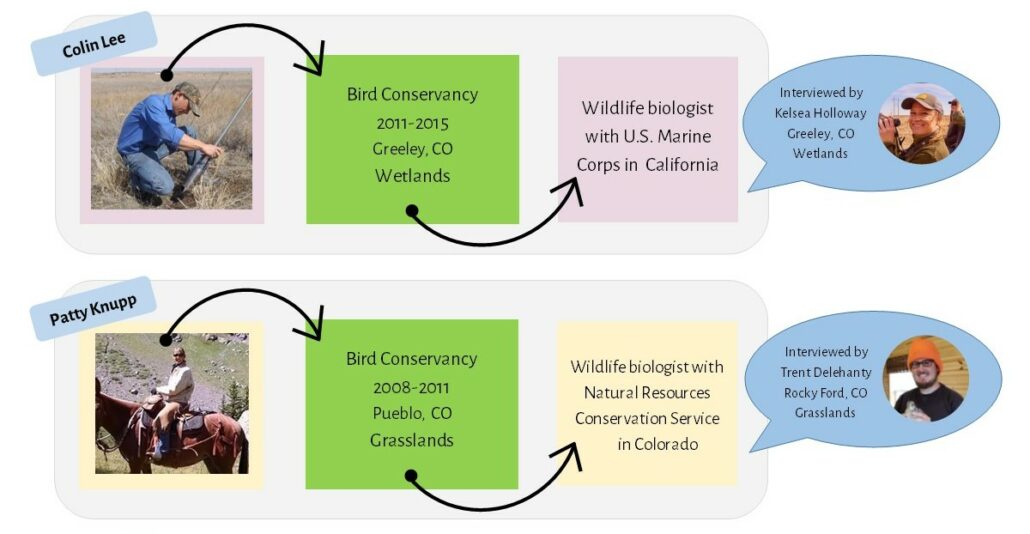

Recently, several of our current Private Lands Wildlife Biologists (PLWBs) visited with their predecessors to hear their reflections on how working as a PLWB for Bird Conservancy influenced their future career path. We wanted to capture insights that might be useful to our current cohort of biologists, and were seeking inspiration after all the challenges of working in people-centric conservation during a global pandemic. We also wanted to better understand how the unique nature of our partner-biologist model sets these conservationists up for future success in their endeavors.

Some of the folks we spoke to had worked for Bird Conservancy as far back as the genesis of our PLWB program back in 2008, and some had left the organization as recently as 2020. All are still currently employed within the conservation field, with the exception of one who has recently transitioned to being a full-time agricultural producer! Check out their career progressions throughout this post to see where our PLWBs have landed.

The Road to Bird Conservancy

The Road to Bird Conservancy

Many folks in the conservation and wildlife biology fields have winding career paths. Several of the PLWBs interviewed had common themes among their experiences prior to working as biologists with Bird Conservancy. Several worked seasonally for state wildlife agencies like Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), including Brandon Miller and Becky Jones, who both researched Greater Sage-grouse on private land in northwestern Colorado for CPW. Others had recently wrapped up Master’s degrees, like Marty Moses and Kelly Corman. Kelly studied Lesser Prairie-chicken on private land for his thesis, and was one of several folks who had direct experience with a species that would later become the focus of their work as PLWBs. Others had experience with agencies and organizations such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, local Conservation Districts, and Pheasants Forever.

- Greater Sage-grouse. Photo from USFWS.

- Lesser Praire-chicken. Photo by Larry Lamsa (CC by 2.0).

Lessons Learned Along the Way

Our land stewardship positions allow for both professional and personal growth and development. We asked the former biologists to reflect on what they learned while working for Bird Conservancy that was useful in their subsequent positions. There were two major themes which nearly all the former PLWBs mentioned: the importance of working with partners to achieve conservation goals, and learning how to build relationships with landowners. State wildlife agencies like Colorado Parks and Wildlife, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, Nebraska Game and Parks Commision, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, South Dakota Game, Fish, and Parks, and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks are all key partners to achieving wildlife habitat conservation.

Brandon Miller, who now works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Partners for Wildlife program in Colorado said, “The people side of it is probably the most important part to getting stuff done on the ground…I don’t think that most of us get into the wildlife field to work with people, but it is crucial.”

Brandon Miller, who now works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Partners for Wildlife program in Colorado said, “The people side of it is probably the most important part to getting stuff done on the ground…I don’t think that most of us get into the wildlife field to work with people, but it is crucial.”

Others enjoyed getting to learn a variety of new technical skills that allowed them to become a jack of all trades beyond their expertise in wildlife ecology, from hydrology to engineering to range management. Becky Jones also reflected on the benefits and opportunities provided from working in a highly flexible and independent role: “It built my confidence, and my ability to build my own program, and run it, and choose what direction to take it.”

Former PLWB Colin Lee conducting elevation surveys for slough restoration planning in northeastern Colorado. Photo by Lynn Lovell, NRCS engineer, 2015.

Working with private landowners

Building relationships with landowners was one of the most important and enjoyable aspects of the job for many of those we spoke with. Several of our past biologists reported that they still keep in touch with landowners they built a rapport with. For example, former PLWB Patty Knupp is now an Area Wildlife Biologist for NRCS in Colorado where she works with Chico Basin Ranch, a partnership she developed during her days as PLWB.

Resource professionals and ranch hands plant native cottonwood poles as part of a riparian restoration at Chico Basin Ranch, Colorado in 2011, an effort that was pioneered by former PLWB Patty Knupp.

Creating these relationships and establishing a rapport with landowners can happen in unexpected ways. Andrew Pierson, a former biologist in eastern Nebraska observed, “I think people can be quick to assume that we as conservation professionals want to change what they’ve been doing for decades on their ranch. But it’s sort of the opposite. We want that ranch to stay a ranch in essentially the same form forever – that’s the best conservation outcome.” Working ranches represent some of the last remaining large tracts of contiguous grasslands in the Great Plains, and provide crucial habitat for birds like Western Meadowlark, Cassin’s Sparrow, Baird’s Sparrow, and Thick-billed Longspur.

- Western Meadowlark. Photo by Deanna Beutler.

- Cassin’s Sparrow. Photo by Bill Schmoker.

- Baird’s Sparrow. Photo by Rick Bohn.

- Thick-billed Longspur. Photo by Bill Schmoker.

Several of the former PLWBs highlighted how much they learned from the landowners they worked alongside, and how bringing an open mindset helped built trust. Kelly Corman said, “Every time you interact with a landowner, the learning goes two ways, and if you approach it with that attitude, you get more out of the it and they respect you more.”

Andrew Pierson also brought up the importance of being respectful towards a landowner’s current operation, saying “In all likelihood, they’re doing it the best way that they think they can. When we get in trouble is when we enter into conversations when we immediately give advice (rather than listening first).” Finally, Becky Jones reflected on learning while touring ranches with the landowners, who had intimate knowledge of the land, knowing where water would flow and when it would come, totally in tune with the cycles of every season.

Andrew Pierson also brought up the importance of being respectful towards a landowner’s current operation, saying “In all likelihood, they’re doing it the best way that they think they can. When we get in trouble is when we enter into conversations when we immediately give advice (rather than listening first).” Finally, Becky Jones reflected on learning while touring ranches with the landowners, who had intimate knowledge of the land, knowing where water would flow and when it would come, totally in tune with the cycles of every season.

Andrew Pierson demonstrates how to install a stock tank ladder, which allows birds and other animals that become trapped in the tank to climb out to safety. The stock tank ladder was designed by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, and simple conservation measures like this can help build a rapport with landowners that can lay the foundation for even more impactful habitat management work.

Taking Flight to New Roles

The cohort of folks we interviewed worked in their positions as PLWBs for an average of 4.5 years before deciding to move to their next role. Half of those we talked to decided to move on because they were starting a family and wanted to return to their home states to be closer to extended family. Several moved to other nonprofits like Audubon, Pheasants Forever, and the Northern Prairies Land Trust, while others moved to agencies like Nebraska Game and Parks, NRCS, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Half of the former PLWBs we talked to continue to work with private landowners doing habitat management.

- Becky Jones left Bird Conservancy in 2018 to become a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service in Alaska. Photo courtesy of Becky Jones.

- Since leaving Bird Conservancy, Kelly Corman has worked with Nebraska Game and Parks in several roles, including private and public land management. Photo courtesy of Kelly Corman.

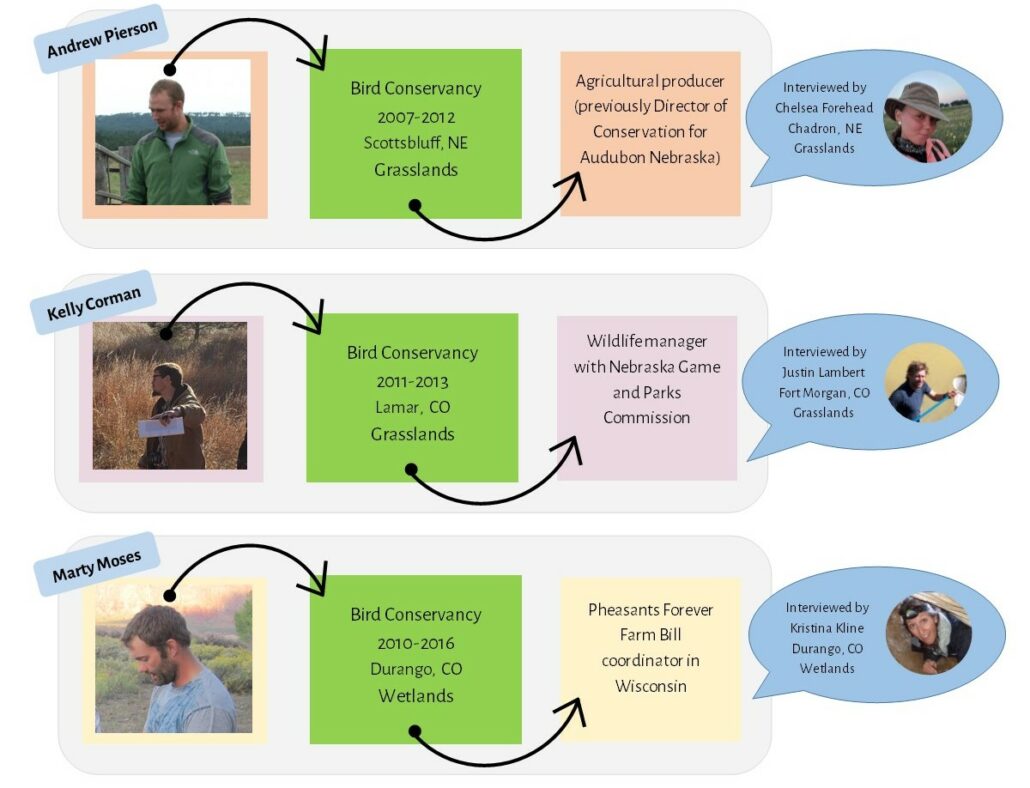

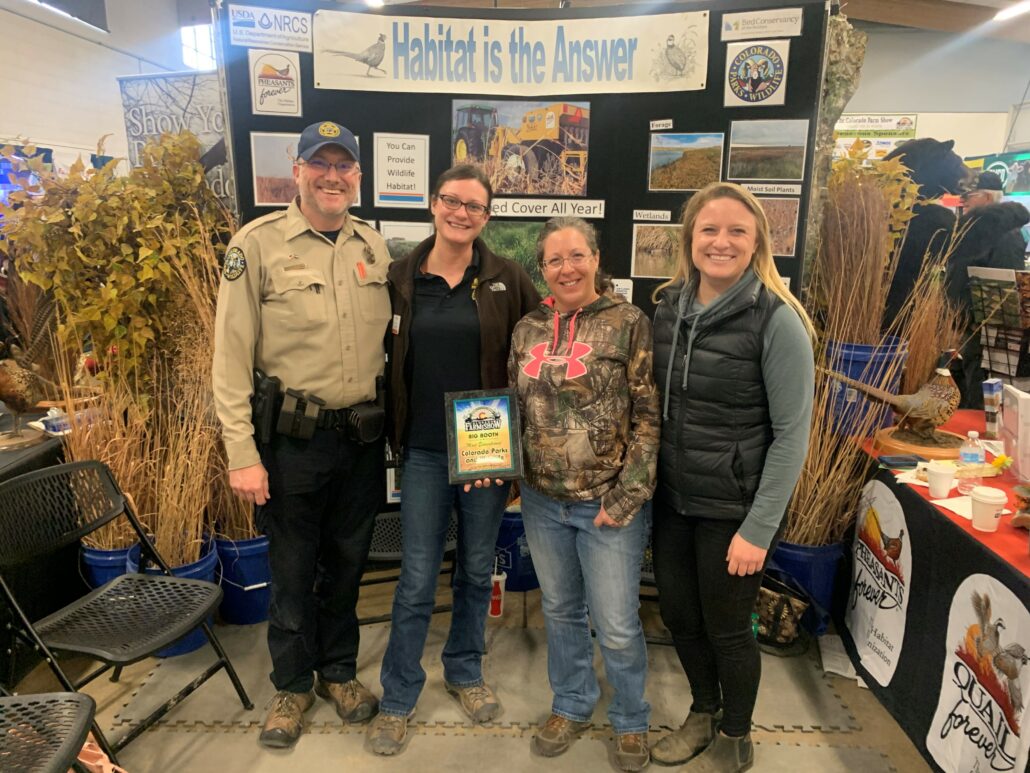

No matter where they’ve ended up, the skills they gained and the experiences they lived through as PLWBs have shaped the contributions these enthusiastic biologists have made to the conservation of birds and their habitats. When we hear about issues like expanding human development, wildfires, and invasive species, it’s easy to throw up our hands and think these problems are unsolvable. Luckily, biologists like the ones we interviewed are steadfast in their work to conserve and restore habitat with the hopes of reversing the decline of wildlife populations. These biologists laid the foundation that is carried forward by our current team of biologists, who continue to build relationships with landowners and develop partnerships, and many thousands of acres of private land are better for it.

Current Stewardship biologist Kelsea Holloway (right) hosted a booth at the 2020 Colorado Farm Show with former Stewardship biologist Noe Marymor (center right) along with staff from Colorado Parks and Wildlife (left) and Pheasants Forever (center left). Noe is currently an Area Biologist with Colorado NRCS. Photo courtesy of Kelsea Holloway.