Prairie grassland in Colorado | Photo: Trent Delehanty

Driving backroads in eastern Colorado, vast expanses of open grasslands stretch toward the horizon. Some areas conjure pastoral scenes with miles of fencelines enclosing herds of cattle, while other fields are seemingly empty seas of grass until you spot a pronghorn in the distance or hear a Western Meadowlark’s bubbling song. Experienced birders know these fields are treasure troves on spring days, with plain brown Cassin’s Sparrows performing extraordinary display flights and Grasshopper Sparrows defying gravity to cling to thin blades of grass while throwing their heads back in song.

Most of these grasslands, like the majority of the Great Plains, are privately owned. Behind each parcel are the stories of individuals and their families, stewards of the land who must consider more than just scenic qualities and the inherent beauty of the wildlife that lives there. Livelihood, productivity and conservation are just a few of the motivations that landowners must balance when making decisions about how to manage their land. Across the Great Plains, a long history of converting native grassland to crops has resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of acres of habitat. Fortunately, conservation programs exist to help restore converted fields back to grassland.

Conservation Reserve Program

Established in 1985, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is one of the USDA’s largest voluntary conservation programs within the Farm Bill. CRP provides a rental payment rate per acre to agricultural producers, in exchange for taking marginal land out of crop production and planting grass cover for a term of 10-15 years. Many landowners find CRP to be a win-win. Marginal cropland is often plagued by erosion (a legacy dating to the Dust Bowl), and enrolling in CRP enables landowners to balance soil conservation with the need to generate stable financial returns from their land. This helps landowners sustain or grow their farming or ranching operations, keep their land in the family for future generations, or to retire from farming altogether. A 2019 social science study showed that land management outcomes—preventing soil erosion, improving soil health, maximizing profits, and improving wildlife habitat—all play a role in landowner willingness to participate in CRP.

“Expiring” CRP Acres

“Expiring” CRP Acres

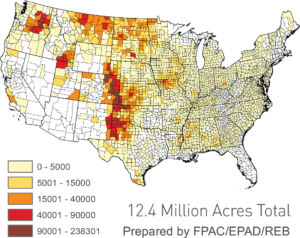

Despite the benefits CRP represents for soil health, wildlife habitat, and landowner livelihood, the program has been struggling. This 2016 report shows that since 2008, the acreage enrollment cap allotted to the program has been decreased by almost 13 million acres. While interest in CRP re-enrollment remains high overall, many landowners find it difficult to qualifying for re-enrollment due to increased competition for limited program spots.

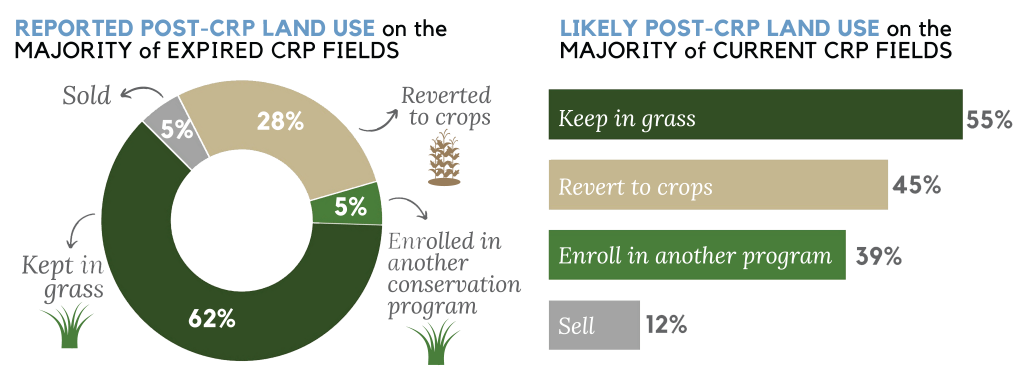

Most landowners (83%) with current fields expressed a desire to re-enroll, yet more than half (54%) with expired contracts that tried to do so were not successful.

The Great Plains has some of the highest rates of CRP participation in the nation. Between 2020-2022, Colorado alone is slated to have 1.4 million acres of CRP contracts expire as enrollment agreements come to an end, much of which is located in the state’s eastern plains.

Declining CRP acres = habitat loss

When a CRP contract ends, landowners can take a variety of paths forward, such as applying for re-enrollment, reverting to crops, transitioning to grazing, or enrolling in other NRCS conservation programs. Land returning to crop production or developed for other uses represents a loss of grassland wildlife habitat, while re-enrolling in CRP or transition to grazing would allow the land to remain in grass cover. Landowner decisions following CRP are shaped by many factors, not the least of which are economic pressures and social influences.

Rancher Dwight Abell shares his thoughts on the Conservation Reserve Program | Video: Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative

According to the CRP Fact Sheet, landowners who chose to keep their fields in grass cover after their contract expired shared two traits in common. First, these landowners had access to resources, especially those related to grazing infrastructure like water and cattle. Second, these landowners were highly motivated to prevent soil erosion. This is great news for those who care about grassland wildlife habitat, because it demonstrates that transitioning to grazing is a viable option if we can connect landowners to the resources and expertise they need to make the change.

“I watched that [land] blow too many years. We’re not gonna plow it up.” ~landowner quote from practitioner focus groups in 2020 emphasizing the role of preventing soil erosion in decision-making

Expanding the network of Private Lands Wildlife Biologists

With support from the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation’s inaugural Colorado RESTORE program, the Natural Resources Conservation Service and other generous funders, we recently hired two new Private Lands Wildlife Biologists in eastern Colorado. These biologists work closely with the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the Farm Service Agency to provide landowners with viable options to keep their fields in grassland habitat once their CRP contracts expire.

In addition to salary support, the grant provides funding to help landowners transition to wildlife-friendly grazing operations by paying for infrastructure like fencing and water development. These actions align with landowner values and motivations, including soil conservation, financial stability, and habitat improvement.

Birds and CRP: Making the Connection

Birds and CRP: Making the Connection

The U.S. and Canada have lost almost 3 billion birds since 1970, with grassland bird species suffered the steepest declines, losing an estimated 53% of their population, or more than 720 million birds. Although not originally intended as a wildlife-focused program, CRP has been revealed as very important to birds that rely on grassland habitat. Bird Conservancy scientists recently studied the benefits of CRP participation to wildlife habitat in the southern Great Plains. They found grassland birds were more abundant on CRP-enrolled lands, which supported higher avian biodiversity than other agricultural lands. The study confirms the value of CRP to create habitat benefiting birds suffering serious population declines.

Looking ahead

We look forward to building on successes in eastern Colorado as our biologists become trusted community members, advocating for a bird conservation model that equally values the role of ranchers and landowners in the process. And to the private landowners engaging in voluntary conservation, we extend a hearty thanks for your efforts!

Thank You Colorado RESTORE grant partners!

and many other generous funders!

Pronghorn, a symbol of the grasslands. | Photo: Jessie Reese