Following Grassland Birds from the Chihuahuan Desert to the Northern Great Plains

By Erin Strasser, Biologist, International

The story of grassland birds isn’t an easy one to hear. Native grasslands are being torn up for agriculture, overgrazed, suffering drought, taken over by invasive species, and experiencing shrub encroachment—leaving many bird species with a mere 10% of their populations remaining.

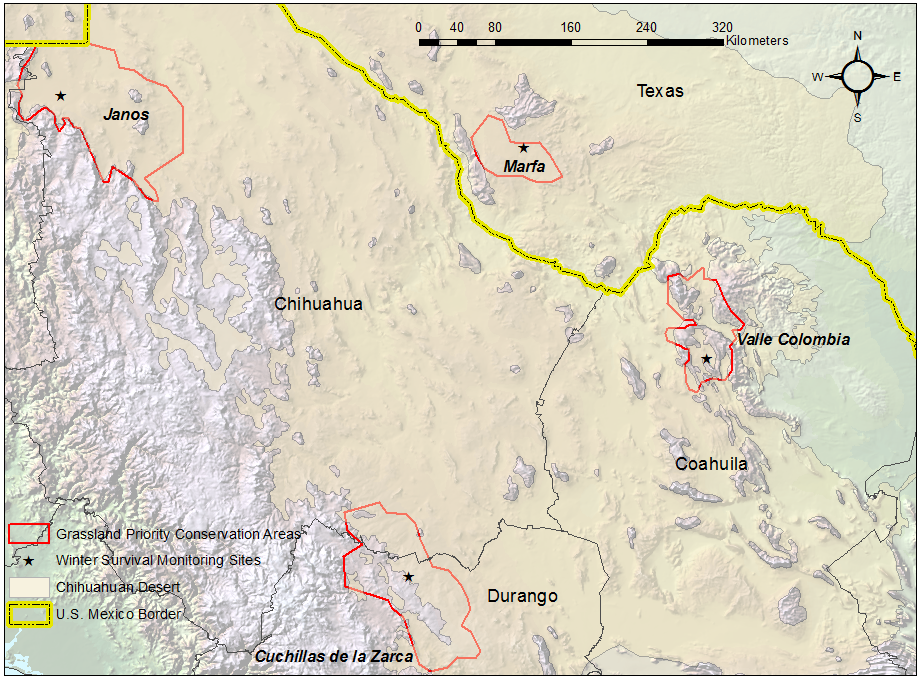

Figure 1: Study areas within Chihuahuan Desert Grassland Priority Conservation Areas (GPCAs): the Janos GPCA, Chihuahua, MX, Cuchillas de la Zarca GPCA, Durango, MX, Valle Colombia GPCA, Coahuila, MX and the Marfa GPCA, Texas, USA.

Bird Conservancy and its partners from the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, and Sul Ross State University’s Borderlands Research Institute are finishing up another winter of grassland bird monitoring in the Chihuahuan Desert. This project, which began in winter 2012-13 uses radio-telemetry to provide insights into factors that impact winter survival of Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows. Basically, we capture birds, tag them with radio transmitters and follow them to get an insider view into their lives. In truth, sometimes we feel a little bit like sparrow paparazzi.

A Northern Harrier prowls the grasslands in search of prey. Photo by Isaac Morales

The species that winter in the Chihuahuan Desert eke out a fragile existence. This desert is harsh and during the winter, contrary to the breeding season when the sparrows focus on defending territories and raising young, the majority of a bird’s energy is invested in survival. Without dense grass needed for cover from predators and insulation from the cold, as well as a decent food supply of grass seeds, these little birds can easily perish to cold or predators. Those that do survive may not have the energy reserves to return north the breeding grounds or do arrive but fail to raise nestlings.

Fortunately, in comparison with previous field seasons this winter has treated the birds well. As of late February, only 29 of the 298 sparrows are confirmed to have perished to predators such as Loggerhead Shrikes and Northern Harriers. In sharp contrast, by this time in winter 2015-16 almost 48% of the 260 tagged birds had died! Better grassland conditions at many of the sites and milder temperatures have likely helped the birds survive the season.

Especially exciting for this year is that we’ve documented a few birds returning to their winter homes. One Grasshopper Sparrow was originally banded in December 2013. A Baird’s Sparrow which we tagged and tracked from December 2015-March 2016 returned to his same small territory located in prime grassland real estate. He is currently wearing his fourth ever radio-transmitter!! Both will be tracked until mid-March when they will be captured prior to migration

We’ve also tracked four Sprague’s Pipits, another species in steep decline and seven Loggerhead Shrikes (pictured here) — a primary predator of wintering sparrows. Photos by José Hugo Martínez

What’s next?

From here Bird Conservancy will shift its efforts to these species’ breeding grounds in the Northern Great Plains. We will monitor nests, fledglings, and breeding adults in Montana, North Dakota, and Alberta, Canada. This project is really one of a kind; we monitor these drastically declining and understudied species through their full life cycle at a tri-national level! With this data we hope to figure out the best way to conserve these species and their grassland habitat.

In contrast to the wintering grounds, grassland bird habitat in the Northern Great Plains is a lush green. Photo by Erin Strasser

With this winter’s higher winter survival rates we can only hope that more Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows will return to the breeding grounds. This would be especially valuable if birds tagged with geolocators, devices that allow us to determine their migration routes and wintering sites, return. We’ll find out this June when Bird Conservancy and partners from Audubon, Oklahoma State University, University of Manitoba and Canadian Wildlife Service travel to the Northern Great Plains to recapture birds with geolocators.

Stay tuned to see what the breeding season has in store for the birds!

A Grasshopper Sparrow takes off after being tagged and banded. Photo by Isaac Morales

Thanks to our various funders, supporters, and partners including The U.S Fish and Wildlife Service NMBCA, The U.S. Forest Service International Program, Canadian Wildlife Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife, The Nature Conservancy, WWF Fundación Carlos Slim, and the Secretária Educación Pública: Programa Rédes temáticas de colaboración.

The team works to trap sparrows using frisbees and bamboo poles decorated with flagging. Believe us, they work! Photo by Isaac Morales

Watch this amazing video footage which demonstrates how we capture birds and then track them with antennas to understand their lives on the wintering grounds. Footage captured by technician Isaac Morales

About the Author

Erin’s passion for research and avian conservation has led her to study birds in several Western states, as well as Belize and Honduras. She is interested in how anthropogenic change impacts breeding bird behavior and physiology, and the overwintering ecology of migratory birds. This is her 6th year studying overwintering survival and habitat use of Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows in the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands of Mexico. During the winter months, look for Erin and her puppy pal, Merlin, south of the border—then returning to the north during summer to study the same birds on the breeding grounds!